asbestos cement

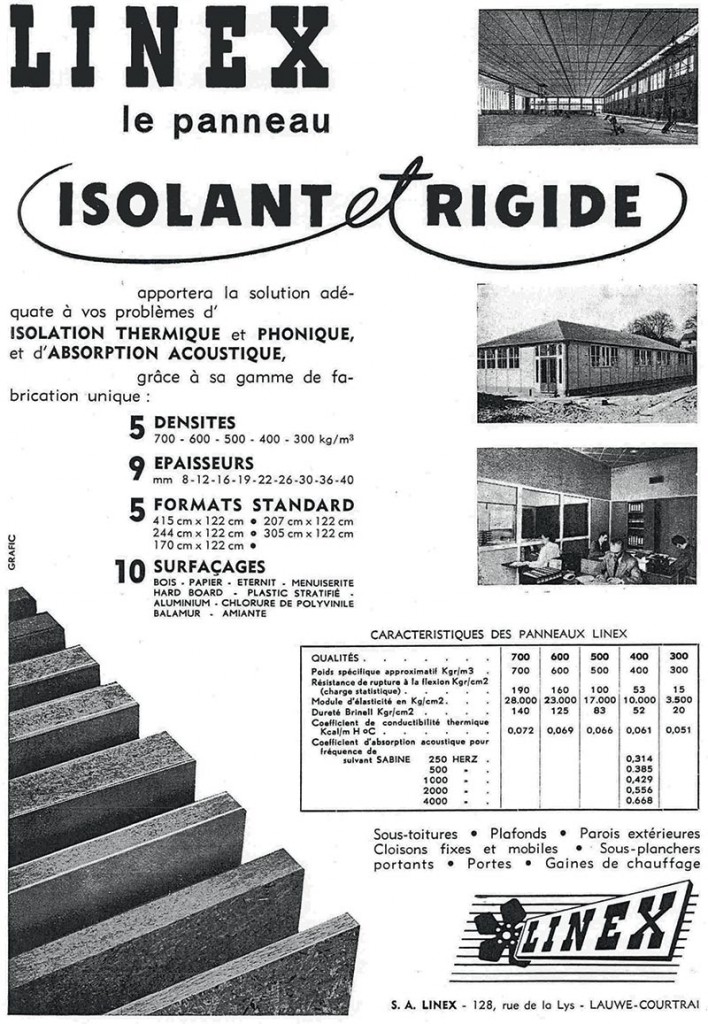

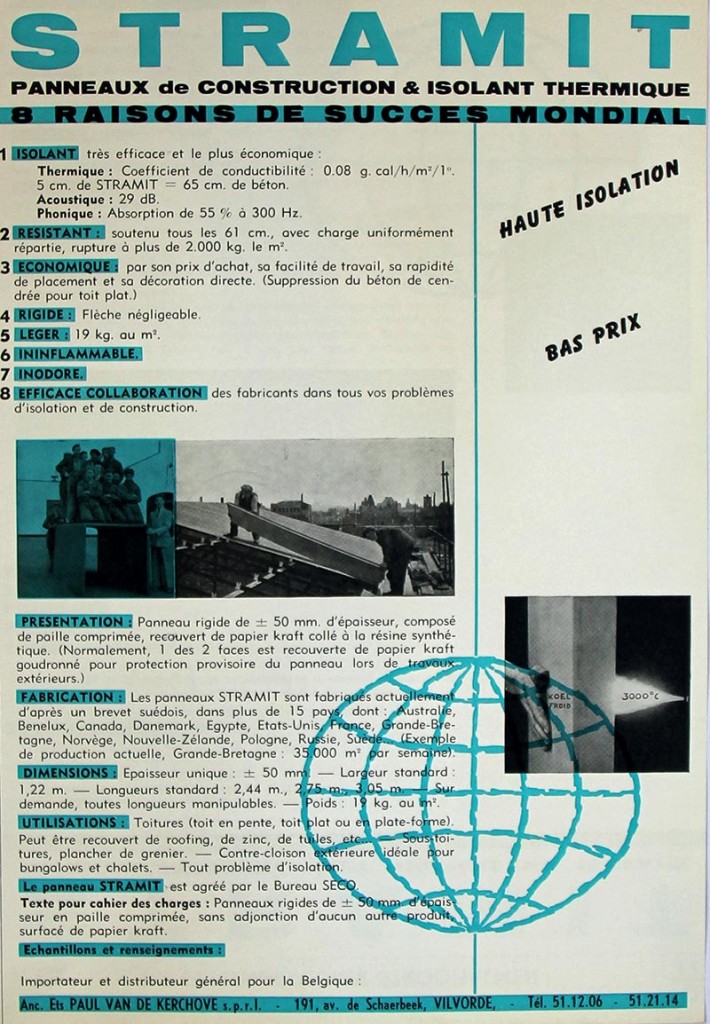

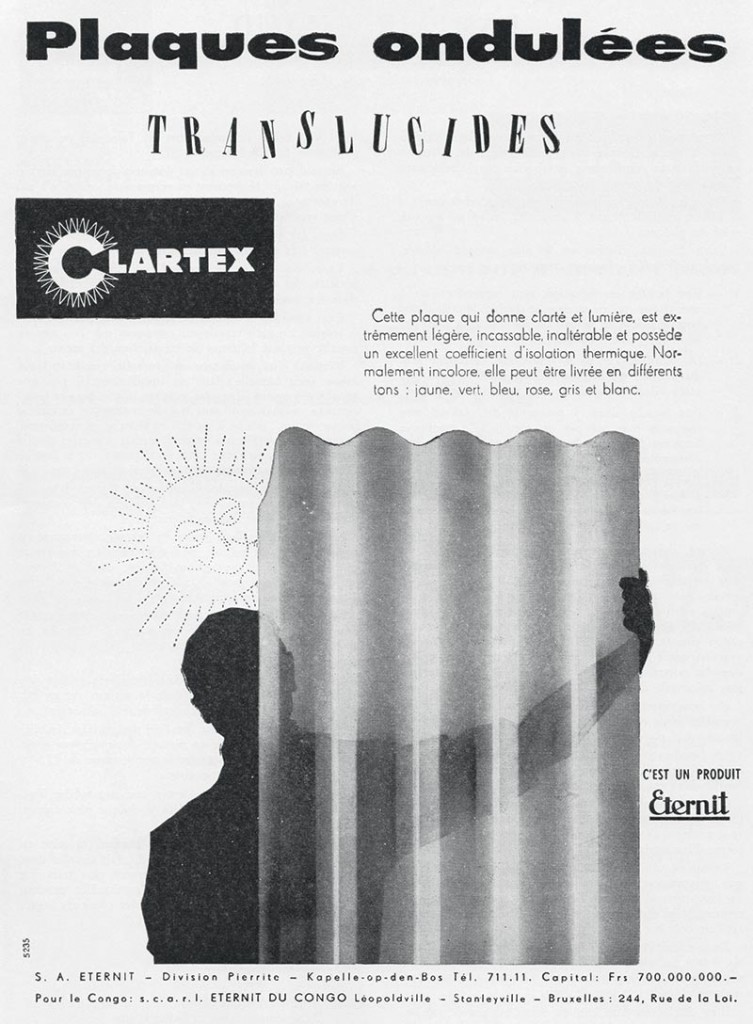

Asbestos also was used widely in the post-war period. Asbestos is a silicate mineral, excavated from asbestos mines, and consists of long, thin fibres that are composed of microscopic fibrils. Bound with cement, it was a versatile, strong, durable, noncombustible, rot resistant, and waterproof building material. The asbestos fibres acted as reinforcement for the cement, increasing its tensile strength to approximately 15 N/mm² and bending strength to 40 N/mm². To produce asbestos cement, asbestos fibres were mechanically converted into pulp and mixed with cement (85 to 90% cement and 10 to 15 % asbestos fibres). The asbestos cement paste was then moulded, compressed by hydraulic presses, and cut to the right dimensions before being stored until the cement had completely set. Despite health warnings about asbestos, beginning in the early 20th century, the use of asbestos cement increased continuously until the late 1970s. But finally the general understanding of the health risks related to asbestos fibres (i.e. the microscopic fibrils, which damage lung tissue when inhaled and can cause cancer) led to a dramatic decline in asbestos production, followed by a ban of its use in many countries in the late 20th century. Manufacturers of asbestos cement products in Belgium were Eternit, Scheerders van Kerckhove, Johns Manville, Alfit, Modernit, and Coverit.

Eternit produced asbestos cement products from 1905 onwards in Haren (near Brussels), under a license from the Austrian Ludwig Hatscheck, who patented asbestos cement in 1901. The production of roof slates and flat panels in asbestos cement soon expanded, and a second plant was erected in 1923 in Kapelle-op-den-Bos. Asbestos cement products were created for a range of applications, including roofs, wall linings, balconies, industrial applications, and even furniture and interior decoration. In addition to the many variations of the ‘regular’ Eternit panels that were developed in the interwar period, the range of Eternit products was expanded in the post-war period and included the enamelled Glasal panels (produced by Eternit Emaillé). The company also diversified its activities and, beginning in 1957, produced plasterboard through a subsidiary company Gyproc-Benelux. Eternit also co-founded Fademac, which focused on the production of flexible plastics for walls and floors based on asbestos and PVC, and Plastic-Benelux, a manufacturer of raw materials for plastics and synthetic materials.

Eternit’s first ‘hit product’ was the standard, flat panel called Eternit. Serving as a substitute for wooden planks and boards, the panels could be processed easily (sawed, drilled, and broken along a pre-cut groove) and were fireproof, rot-proof, impermeable, and hardwearing. Panels were made in thicknesses from 3.2 to 20 mm; they weighed an average of 10 kg/m² (for 6 mm panels). The λ-value was equal to 0.25 W/mK. Panels were offered in double compressed, single compressed, or not compressed versions. Double compressed panels had a very smooth surface and were more flexible as well as stronger, with a failure load 40% higher than single compressed panels. The panels were used for construction works (concrete formwork) as well as interior applications such as doors, furniture, wall linings, paneling, window sills, and ceilings. Panels were screwed on a wooden frame, lath, or blocks, or glued to a lattice or a flat surface. Joints were finished ‘cold’, overlapping, or covered with strips in Eternit, wood, plastic, or aluminium. Most variations to this standard panel were processed and attached in the same ways.

Eternit’s flat panels called Eflex were coloured in the mass (grey, red, green, and yellow) and highly resistant to wear because of the double compression process. Eflex panels were made in three thicknesses (2, 3.2, and 5 mm) with corresponding weights (4.35, 6, or 10 kg/m²). As the brand name suggests, Eflex panels were very flexible. They were used for wall linings, ceilings, floors, doors, countertops, and furniture.

Eternit made other special purpose panels in asbestos cement during the post-war period. Its decorative panels with textured surfaces included a ribbed Eternit panel (5 mm thick, weighing 9 kg/m²), Acimex panels (with grains of sand embedded in the surface), Granite panels (with coloured mineral grains embedded in the surface, 5 mm thick and weighing 10 kg/m²), Elo panels (for wainscoting, mimicking wood), Exterelo panels (for exterior uses), and Elostone panels (for walls and fireplaces, mimicking natural stone).

Eternit developed a complete range of products for roof constructions, e.g. the Romana and Gallia roof panels (large yet very thin and lightweight flat panels), the Ardex corrugated panels, and Doublex roof boarding. The Ardex corrugated panels, on the market since 1952, came in a grey, pink, ‘havana’, and green, and were coated with a transparent, synthetic resin. Within the range of corrugated panels by Eternit, the Ardex panels had the smallest corrugations, only 20 mm high (compared to 31 and 51 mm for the other types). They were also used in facades and balconies. When used in roofs, the panels were often combined with Doublex roof boarding, which were flat boards with special flanges on the side to overlap. The Doublex boards had a smooth, light grey surface. The λ-value of Doublex boards was 0.25 W/mK.

A popular Eternit product was Menuiserite, a panel made of asbestos cement and cellulose fibres, which gave the pink or yellow panels a soft touch. Menuiserite was fireproof, rot-proof, form retaining, watertight, and insulating (λ between 0.19 and 0.21 W/mK). A special feature of Menuiserite was its flexibility, making it ideal for roof sheathing (panels of 2 mm); it was also used for ceilings and wall linings (panels of 3.2 or 5 mm thick). The panels were produced in various sizes, weighing 3.9, 6.2, or 9.8 kg/m². The tensile strength was 9.8 N/mm² and bending strength was 34 N/mm². Menuiserite is still being produced by Eternit today but without asbestos (the letters NT, short for New Technology, are applied to those building materials in which no asbestos is used).

Eternit’s asbestos cement products for flooring (or other applications in which a high wear resistance was important) were Massal, the hollow elements ACE, and ‘333’. Massal was a durable, solid panel and practically indestructible. It was coloured in the mass (in white, grey, red, yellow, and green), strongly compressed in a hydraulic press, and autoclaved. With a thickness between 10 and 40 mm, Massal weighed 20 to 80 kg/m². In addition to floors, Massal was used for thresholds, skirting boards, window sills, fire-places, stairs, and façade cladding. It was fixed to the loadbearing wall or floor structure like a stone veneer, with hooks or anchor rods in iron or copper, which were embedded in the loadbearing structure and fixed to the Massal plates with cement. Similar to Massal, but only available in black with a slightly textured surface, was ‘333’, used for floors and fire-places. The hollow elements ACE, coloured beige and lightly textured, were mainly used for stairs and fire-places. ACE stands for Amiant Ciment Extrudé, referring to the extrusion process with which these hollow elements were fabricated.

The Eternit product that is probably most closely linked to the colourful image of post-war architecture in Brussels is Glasal. Put on the market in approximately 1957, Glasal is a double compressed, autoclaved panel intended for inside as well as outside applications. The panels had a top layer of colourfast enamel, applied with a spray gun, and vitrified in an oven. Glasal also was watertight, damp-proof, insulating (λ = 0.3 W/mK), smooth, easy to clean, rot-proof, and resistant to scratches, shocks, acids, grease, solvents, frost, and heat. Despite being very stiff (with a bending resistance of 49 N/mm²), Glasal panels were easily worked with ordinary tools like saws and drills. At 3.2 mm thick the panels weighed 7 kg/m²; other thicknesses, from 5 to 12 mm (weighing 10 to 24 kg/m²), were available on demand. Glasal panels existed in 30 colours, including solid colours as well as speckled, marbled, and linen patterns. Eternit offered a 10 year guarantee on the resistance and durability of Glasal. At the end of the 1960s, the panels were being exported to 50 countries.

Eternit also produced perforated Glasal panels, Glasal S panels (with a slightly rough finish of the enamel, available in 10 colours), and Glasal sandwich panels. The sandwich panels were composed of an outside layer of Glasal, a core of insulation (polystyrene, cork, flax fibre, expanded polyurethane foam, or mineral wool, with sometimes an extra damp-proofing), and an inside surface of Glasal, Eflex, Pical, or another Eternit panel. For example, a 27 mm sandwich panel made of two Glasal panels and a polystyrene core had a K-value of 1.23 W/m²K and weighed 14 kg/m²; if the polystyrene core was 40 mm instead of 20 mm, the K-value decreased to 0.71 W/m²K and the weight was 16 kg/m². Glasal sandwich panels were especially used in curtain walls and façade frames, taking the necessary precautions for expansion and water tightness (with putty, mastic seals, Thiokol, silicone, synthetic foam, a glazing bead, etc.). The panels could also be screwed onto a wooden structure (overlapping or with strips to cover the joints). Inside, the panels could also be glued to lath or a smooth surface (with polyvinyl acetate, epoxide glue, contact adhesive, or resorcinol).

Scheerders Van Kerchove (SVK) was another important manufacturer of asbestos cement cladding and sandwich panels. Like Eternit, they produced a wide range of products, including the regular panels SVK; decorative panels; corrugated plates; flat panels; sandwich panels called Multiboard; flexible panels in asbestos-cellulose Novex; elements in ‘granito’; Ceram and Marbrabel floor tiles; and artificial slate. Three different types of decorative panels were developed: Ornit, Lambriso and Ornimat. Ornit panels, offered in several lively colours, were mainly used in living areas. Lambriso panels imitated oak and were mainly used for wainscoting. Ornimat, the most popular of SVK’s decorative panels, was a flat, compressed panel with a solid, smooth, and shiny top layer of polyester, which was cured by means of polymerisation. Ornimat was impermeable, fireproof, durable, strong, rot-proof, colourfast, and resistant to low and high temperatures. The panels came in 20 tints, were 3.2, 5, or 10 mm thick, and weighed between 6 and 20 kg/m². Ornimat was used as such or in sandwich panels. SVK’s Multiboard sandwich panels came in two forms: a flat panel (for interior and exterior walls) and a corrugated panel (for roofs). Both were composed of two asbestos cement panels with granules of mineral insulation (possibly mica) in between. The corrugated panels were 122 by 98 cm, 4.5 cm thick and weighed 40 kg per panel. The flat panels were 250 by 120 cm, 3 or 4 cm thick and weighed 85 or 102 kg per panel. According to tests by the independent research laboratory OREX, the corrugated panels could carry a uniformly distributed load up to 1,020 kg/cm. As for the thermal conductivity, empirically defined, the λ-value was approximately 0.13 W/mK for both corrugated panels and the 4 cm thick flat panels.

Other asbestos cement companies produced similar but fewer kinds of products. For instance, Alfit produced single compressed flat panels (between 4 and 10 mm thick), double compressed panels (with two smooth surfaces), corrugated panels, Alfit Incruste (with a decorative pattern imprinted on it), Alfit Granite (with a decorative top layer resembling natural stone), Alfit Marbre (resembling natural marble), Alfo panels (for wainscoting), and Alfit Emaillé (in several plain colours).

A company that did not produce panels itself but incorporated them in a sandwich panel was Atemo. The Atemo Privas panel was composed of a core in expanded polystyrene, with asbestos cement panels on each side and an optional finishing layer or coating. These were used mainly as façade cladding or in curtain walls. The panels were between 2.5 and 5 cm thick and weighed 20 to 25 kg/m². The thermal conductivity K was between approximately 0.58 W/m²K (for 5 cm panels) and 1.28 W/m²K (for 2.5 cm panels). The panels were frost-proof, watertight, resistant to chemical agents, and had good mechanical properties. In addition to the ‘Brut’ version (with grey and cheap asbestos cement panels, without any decorative treatment), Atemo offered a wide range of surface treatments and colours by using, for instance, Glasal, aluminium, PVC, Skinplate, and Temcoat panels. Skinplate, produced by Phenix Works, was a thin metal or aluminium sheet onto which a thin coating of PVC was applied. Temcoat was a coating based on thermosetting resins, died in the mass, intended to minimize dirt adhesion. It was used in the Cité Modèle in Brussels, where thousands of square meters of sandwich panels with Temcoat finish were installed in Chamebel window frames.